Please note that this website is run on a non-profit basis for educational and research purposes. Images are credited with their respective copyright holders where they are known. You may not copy any image for commercial purposes. Please do not ask me for permission to use any images – that permission is not mine to give. If you are the copyright holder for an image and wish it to be removed, please contact me via the form at the foot of the page and I will of course be happy to do so. Also, if you are the owner of an uncredited image and wish to be named, again please contact me and I’ll happily add that information.

LWT’s OB fleet was originally based at Wembley studios (as was Rediffusion’s beforehand.) In February 1971 they moved to a site not too far away in Stonebridge Park. It had previously been the headquarters of a company called Intertel. This company had owned a couple of OB units and had also built a studio on the site in 1966 that could be serviced by their OB cameras and scanners. Intertel had been around for several years but in September 1970 they merged with TVR to become TVI and shortly after left the site, enabling LWT to move in.

Intertel’s staff lighting director, John Burgess, became one of the UK’s first freelance LDs – subsequently working at Ewarts Studios amongst other places. Anyway, this studio in Northfields Industrial Estate, Wembley became the property of LWT. It remained in service for another 13 years and was known by LWT staff as Wycombe Road .

Before looking at the studio itself, it is worth examining the story of Intertel .

Intertel (VTR Services) Ltd was established in 1962 to service the increasing demand by American television networks and independent producers for electronic production facilities in Europe. They were initially based at a site in Ealing where they parked their scanners and also had a small studio. The Ealing premises were called Plant House and were in Longfield Avenue. Peter Dearing tells me that the place was a bit ‘rough and ready.’ He remembers Peter Sellers coming to shoot something in the studio and commenting that the building “looks like Steptoe’s back yard.”

Chris Patten recalls…

‘…at the time I joined them they had two 4 camera monochrome scanners – an EMI 203 and a Marconi MK IV one. They also had a massive two unit scanner based in Switzerland, which later got moved to Ealing. We then built the Marconi colour scanner and then the PC60 one. They ran out of room at Ealing and started looking for a new site. They found the site at Stonebridge Park while it was still under construction as a warehouse. They managed to get the building design changed during the construction stage and raised the roof of the building and added the cafeteria.’

As mentioned above – at first, the camera and videotape facilities were monochrome but by 1964 – when the Innsbruck Winter Olympics coverage for ABC TV was undertaken entirely by the Intertel group of companies – the demand was gradually changing to colour.

In the UK, only Marconi had produced a working colour camera at this time – the BD848. This had been developed from an earlier RCA design in the US. In fact, Peter Dearing recalls that it was known by Intertel as a TK-41, the RCA reference number. Much had been learned during the BBC’s colour experiments at Alexandra Palace from 1955 and later at Lime Grove. The camera in 1964 was still based on image-orthicon tubes but by then was very different from those early models. It now utilised technology developed for the Marconi Mk IV monochrome camera. It was still large and relatively unstable but could produce perfectly acceptable pictures. However – it was clear that the image orthicon tube was not the way of the future for colour TV. Early in 1964, Philips announced its development of the Plumbicon camera tube and later in that year, the design and prototype manufacture of the PC60 camera channel that used three of the new tubes in each camera.

Although the PC60 was smaller, lighter, and required only approximately a 50% increase in scene illumination compared to its monochrome counterparts, the reaction by European broadcasters was lukewarm, since colour standards had yet to be agreed upon. Philips themselves were said to be not particularly helpful and were prepared only to forecast a probable delivery of PC60s in mid-summer 1966.

This situation placed Intertel in something of a cleft stick – a good 75% of their business came from the US networks and affiliates on the West Coast. If they could not meet the demand for colour programming facilities in Europe, the business would be lost.

This left them with no option but to purchase four BD848 cameras from Marconi and to quickly build a scanner to accommodate them. Because of the sheer bulk and weight of the camera control units the front suspension of the vehicle had to be reinforced. The cameras needed a very long warm-up period – Peter Dearing recalls a show made in Maurice Chevalier’s house in Paris when he had to go in at 5.00 am to switch them on and sat there on his own for hours surrounded by priceless Renoirs and Picassos. The Marconi cameras would also suddenly leap out of registration, when a sharp blow to a particular capacitor seemed to do the trick. Peter remembers doing this on a live show from the Palladium.

Although many of the programme assignments which Intertel subsequently undertook for its American clients were outside broadcasts, winter sports etc., the majority were in fact indoors and this posed a whole raft of new problems concerning lighting – the like of which neither Intertel, nor for that matter any other television company in Europe, had encountered before. To put the matter in perspective, monochrome 4.5″ Image-Orthicon cameras in regular studio usage in the mid 1960s required between 1000 lux to 1500 lux to produce good quality pictures. (Today we light at a level of about half that). By comparison, the BD848 using 3″ Image-Orthicon tubes needed a minimum of 3500 to 4000 lux to produce usable pictures – about 6 times today’s lighting levels!

In an attempt to resolve this problem, Intertel built a massive lighting generator – with an overall output of 1200 Amps @ 240v., nearly 300kVA, single phase – to supply scanner, VT truck and lighting too. Apparently, ‘Big Bertha’, as the generator came to be known, on occasion provided standby power at BBC TV Centre. After serving Intertel well, it was probably finally put to good use by their new owners, LWT, as an emergency power source at their new studio centre on the South Bank in London.

This ad from 1968 reads ‘ John Osborne’s Luther shot at Stonebridge Park Studios’ The camera is a PC60.

When the UK adopted the PAL colour system (the US using the more basic NTSC system) Intertel had to modify its cameras so they could be used to make programmes for the domestic market. Peter Dearing tells me that Peter Johnson, resident lighting director and ‘technical genius’ built some PAL encoders from scratch since it was not possible to get hold of any without waiting months for delivery.

During its relatively short life from 1965 to 1968 – OB1C, as the Marconi BD848 colour unit was known, covered many programme commitments including Sunday Night at London Palladium, Hippodrome in 1966 for Associated-Rediffusion at studio 5 Wembley, Ski Jumping at Innsbruck and the Moscow State Circus in Minsk amongst many others. By 1968 however, its operational role at Intertel had diminished considerably. They had taken delivery of the first four Philips PC60s in the summer of 1966 and installed them in a new vehicle. These would be used in their new studio. Then when a further four PC60 camera channels were purchased in 1968, the Marconi cameras were no longer a viable proposition, and were given to various training colleges, such as Ravensbourne College in Kent.

The OB base contained a studio, originally intended to be a warehouse but adapted during its construction – 99 x 75 ft wall to wall. It had very narrow firelanes at each end giving a working space of 95 x 65 feet. There was originally only one control room – for lighting – the production and sound control were in an OB scanner. Production and sound galleries were added later by LWT when they took over.

![]()

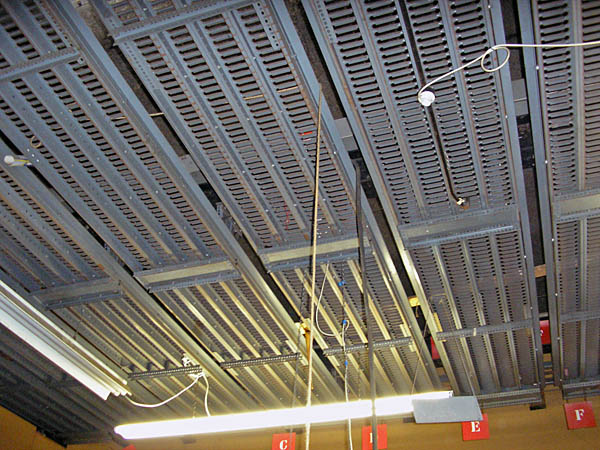

A lighting grid was installed which, perhaps surprisingly, was made partly of Dexion. I found this fact hard to believe until I saw it for myself on a visit in 2006. The grid allowed monopoles to be used with tracks spaced 2ft 6ins apart. There were no crossover tracks.

I gather that the management originally planned to use eggboxes stuck to the walls for acoustic insulation with every member of staff being expected to spend a number of hours sticking them on. Surprisingly, they weren’t too keen on the idea and an alternative solution was found.

Intertel installed a good mix of lights, including some new large softlights called Northlights. These were designed by Des Chalcroft, who it is said also designed the original grid. He formed a small company to manufacture the Northlights – Ballancroft Engineering.

These excellent lights eventually ended up in Lee’s stock and were frequently hired for use on many dramas at Television Centre during the 1980s. A smaller, 2.5kW version was developed which was then sold to Teddington Studios. These softlights were still in regular use well into the 2010s – by me amongst others. Despite their age they were often to be seen lighting sitcoms in the very latest studios in BBC Glasgow and MediaCity Salford as well as at Elstree, Pinewood and TLS.

Incidentally, not all the crew were staff – some were employed on a daily basis, moonlighting from their regular job at the BBC or ITV company. I have been told that it was not uncommon for individuals to sign with names such as Mr M Mouse in order to receive £25 cash in hand for a day’s graft.

Almost all of the programmes made in the studio by Intertel were for the US market. Most are lost and forgotten. One of the earliest bookings in 1966 was for the David Frost Show which was made here for ABC Television. In the same year, Frank Dunlop’s production of The Winter’s Tale was recorded here in colour, starring Laurence Harvey, Jane Asher and Jim Dale amongst many others. Giles Chapman has informed me that an episode of Hammer Films’ 1968 TV filmed series Journey To The Unknown was shot here. It was entitled The Madison Experiment, and the Intertel facilities have a credit at the end. Another episode of that series was called Somewhere in a Crowd. It was filmed in 1969 and features the studio and the OB scanner.

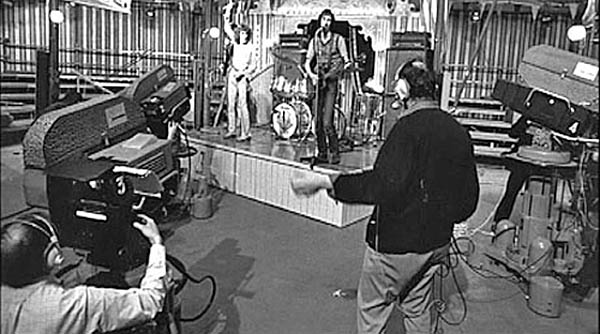

The Beatles performed here in 1966 and were recorded in colour on videotape. There was also another production made here by the Stones in December 1968 that has become almost legendary. It was the result of a project to create a rock concert tour staged in an ‘experimental’ mix of music and circus. The tour never happened but a film was shot. Called The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, it was a kind of concert by the Stones within a circus tent set and with many special guests.

The show included performances by The Who, Jethro Tull, Taj Mahal, Marianne Faithful, Yoko Ono and ‘The Dirty Mac’, a group that was the first musical context in which John Lennon performed before an audience outside The Beatles. The Dirty Mac was Eric Clapton (lead guitar), The Rolling Stones’ own Keith Richards (bass) and Mitch Mitchell of the Jimi Hendrix Experience (drums) with Lennon on guitar and vocals. It was also the last time guitarist Brian Jones performed with the Stones. A few months later he had died. A Blu-ray of this production is available and is highly recommended.

The cameras for this programme were not the usual Intertel ones. They were a curious hybrid of 16mm film camera and black and white video camera. They were operated in a TV style, using electronic viewfinders and mounted on Vinten peds and a Mole crane. They were supplied for this show by a French company and apparently were highly prone to breaking down. The delays in filming caused the show to overrun until 5.30 in the morning.

Amazingly, the processed film rushes were not edited at the time. It seems that despite the success of the show the Stones decided to remake it at the Colosseum in Rome. (Why not?) Perhaps not surprisingly, it proved to be impossible to get permission to film there so the project foundered and the film rushes were left in cans in the Stones’ office. When they moved offices some time later the film cans were moved to a barn owned by the road manager and forgotten. He died some twelve years later and his wife rediscovered them. They were finally edited and turned into an extraordinary film in 1996 that is a unique snapshot of the world of rock thirty years earlier.

There is some confusion over these hybrid cameras. Intertel owned a set of Addavison cameras later on but these French cameras are probably not those. Maybe they thought the principle was sound but they needed some cameras that were more reliable and easy to use.

From 1967 the studio was hired on several occasions by – rather surprisingly – Yorkshire TV to record drama productions. They began broadcasting to the new ITV region in 1968 but their studio centre in Leeds opened with only three relatively small studios. Therefore, until their main studio 4 opened in 1969 they regularly booked this studio.

The blue doors were for scenery access, the central bricked area was the BFBS technical area – the single door was a fire escape. Above the blue door was the canteen, the rest of the first floor was offices for BFBS. The top floor was make-up, wardrobe etc.

The small building on the left was originally owned by a company called ‘Caterers Buying.’ There was a relatively narrow passage between it and the LWT building causing inevitable problems getting the large OB vehicles between the buildings to the yard at the back. Oddly, the building was bought by LWT but left empty and not demolished. This did happen much later, probably when the site was owned by Lee Lighting.

According to Kinematograph Weekly, at the end of April 1969 all the shares in Intertel were bought by London Weekend Television. As well as acquiring this studio, LWT also took over 2 OB trucks. The Kinematograph Weekly report states that LWT planned to use the Addavision system here to film programmes in colour for the export market. Reportedly, Maurice Styles, the MD of Intertel resigned ‘to set up on his own’ but the majority of staff at Wycombe Road remained as employees of LWT.

Curiously, the name Intertel seems to have carried on, probably as a fully owned subsidiary of LWT. In January 1970 Intertel opened VTR recording facilities in Dean St, Soho including a small studio. All the Intertel shares were purchased by TVR to form TVI only a few months later that year but LWT retained ownership of the Wycombe Road studio.

Patrick Neil has noted that the studio was used by LWT in June 1970 when some episodes of series 2 of Ronnie Barker’s show, Hark at Barker, were recorded here.

In 1973 they refurbished the studio – installing production and sound control rooms – and bought some new cameras. Unfortunately, these were EMI 2005s, which were equally unpopular with cameramen and engineers.

LWT’s South Bank centre did not open until 1972, so this studio was used as a back-up to their Wembley studios at first (using an OB scanner for facilities), then continued in use for many years even after their brand-spanking-new studios opened.

It does seem odd to me that LWT should not only spend millions building their new centre on the South Bank but only the year after it opened be spending a not inconsiderable sum on this studio too. They could have continued using it as a basic four-waller, utilising an OB truck for technical facilities – but no. They built new galleries and bought new cameras. One has to wonder why. The studio was never really busy during its time in service. They must have anticipated a regular use that never transpired.

For most of the time that LWT operated the studio it was used as an overflow space to cope with busy periods. Crews came from the South Bank and only a skeleton staff maintained the studio between bookings. Amongst the programmes made here was a big Julie Andrews special that included the Muppets as guests. This show was mainly intended for the American market. Oddly, a very similar programme is said to have been made by ATV at Elstree although that was a Muppet special with guest – Julie Andrews. Spot the difference?

VT engineer Andy Backhouse has confirmed that an Andrews/Muppet special was indeed made here but he continues…

‘…the best thing was that in the early 80s, LWT used to rent the studio to the mega bands and artists as a rehearsal space prior to moving into Wembley Stadium. Whilst working on the most lucrative part of my career at BFBS, I and my colleagues spent many a night on the lighting mezzanine watching and listening to virtually private performances by the likes of Dire Straits, Rod Steward, Madness, Boomtown Rats, Tina Turner etc etc. They even built the entire lighting and stage rigs in the studio!’

Other shows recalled by LWT staff include a sitcom set in a railway station called The Train Now Standing starring Bill Fraser and a drama The Death of Adolf Hitler (1972) starring Frank Finlay. There was also a Hoover commercial and several plays for US television directed by Terence Donovan.

LWT also rented the studio to other companies including Anglia for some Tales of the Unexpected.

Apparently the studio was a popular place to work and had excellent catering. (You may have noticed that this is a recurring theme throughout this history. All I can say is that when you are working a fourteen hour day there is nothing more depressing than going to the canteen for supper and finding that everything on offer is inedible.)

BFBS

On the ground floor of the office block on site was a small studio (about 350 sq ft) used by the British Forces Broadcasting Service (BFBS). This was not much more than a continuity studio, used to link the programmes broadcast to British forces overseas. They had their own crew, except for one LWT electrician scheduled from the South Bank on a daily basis. This contract ran from 1976 to 1985.

BFBS television then moved from Wycombe Road to a purpose built centre at Chalfont near Gerrards Cross in Buckinghamshire. Those studios were run for several years by a charity called Services Sound and Vision Corporation or SSVC. They were later taken over by the Arqiva group.

At Chalfont there were two studios – studio 2 was 1,250 sq ft (39 x 32 ft) and studio 3 was a VR studio and was 880 sq ft (32ft 6ins x 27ft).

In the summer of 2006 Camelot began a long term booking in studio 2 to use it for the live Lotto draws. Previously these had usually come from TV Centre but following the ‘invasion’ by Fathers for Justice during a live Jet Set in TC4, Camelot looked for a more secure studio. They didn’t come much more secure than that one.

In 2013 Camelot left Chalfont to go to Pinewood – an equally secure studio, purpose built for them (TV-Three). It seems likely that Arqiva closed the studios on its Chalfont site shortly after this.

In 2025, the Lotto draws moved to a small purpose-built studio at Television Centre.

LWT’s EMI 2005 cameras and all the gallery sound and vision equipment soldiered on from 1973 to 1983 when LWT began seeking a joint venture with a facilities company to modernise the studio. They were probably hoping to attract work for the newly-opened Channel 4. This unfortunately came to nothing. In September 1984 the studio was sold for £1m to Joe Dunton Cameras but they didn’t actually move in until the following year. LWT’s OB fleet transferred to new premises in Acton in March 1985 and, as mentioned above, BFBS moved to Chalfont.

Joe Dunton Cameras was a division of Media Technology International (MTI) in which Lee Electric held a stake of 52.53 per cent. This business specialised in camera rental but the studio gave them the opportunity to expand their business. They spent £300,000 refurbishing the site – including the construction of a new camera rental facility. Their original intention was to use the studio as a ‘day-shoot four waller’ but along came a request from a production company who were making a show for Channel 4. The show – ECT – needed a large studio for a 10-week booking. The programme was a live heavy-metal based music show. Apparently everything on the set had an appropriately sleazy futuristic look – even the camera cowlings and their operators and the heavy metal audience were dressed to suit. Facilities were provided by Trilion.

Joe Dunton became very enthused about the show and realised that with the studio’s links to the Telecom Tower it filled a very useful gap in London’s facilities – particularly for Channel 4 or the emerging satellite channel market. However, whether there were any further TV bookings is not yet known, but any were probably few and far between.

Joe Dunton occupied the site between 1985 and 1989.

The large trucks seen here are those of Lee Lighting.

In November 1989 Lee Electric transferred their lighting hire business here to Wycombe Road from Barlby Road, off Ladbroke Grove, where they had been for about three years.

The studio became the warehouse for much of their lighting stock. Two large doors were knocked through one of the long walls and mezzanine platforms built within it. Incidentally, although the technical equipment in the studio had been scrapped, the lighting monopoles still had plenty of life left in them. It seems that via a circuitous route they eventually ended up at Pinewood in the two TV studios there.

When I visited the studio in May 2006 the first impression was of a warehouse but evidence of the studio’s history remained. I entered from main reception through a soundproof studio door and along the walls the footage markings could still be seen. The grid still covered the whole space and the track identification letters hung from one end. The lighting gantry surrounded the studio and was partly used for storage of seldom-used lights.

In 2008 Lee Lighting merged with AFM to become Panalux and left the site.

Richard Smith contacted me in the summer of 2009 to let me know the sad news that the buildings on the site had been reduced to a pile of rubble.