Please note that this website is run on a non-profit basis for educational and research purposes. Images are credited with their respective copyright holders where they are known. You may not copy any image for commercial purposes. Please do not ask me for permission to use any images – that permission is not mine to give. If you are the copyright holder for an image and wish it to be removed, please contact me via the form at the foot of the page and I will of course be happy to do so. Also, if you are the owner of an uncredited image and wish to be named, again please contact me and I’ll happily add that information.

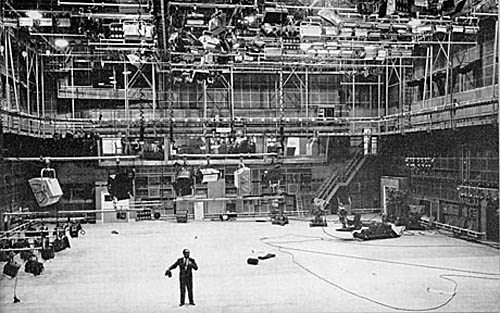

Stage 3 involved the most complex construction and took four years before the Centre became operational. It consisted of the main circular building (the doughnut) and the completion of studios 1 – 7. Four studios would initially be brought into service within the first few months – 2, 3, 4 and 5. The design of these was based on experience gained from working at Lime Grove and in particular Riverside Studios, where various experiments involving gallery layout and lighting systems were tried out. The Centre officially opened with TC3 operational on 29th June 1960. TC2, 4 and 5 opened over the following 14 months in that order. The shells of TC1, TC6 and TC7 were constructed around the same time but they were not fitted out until a few years later.

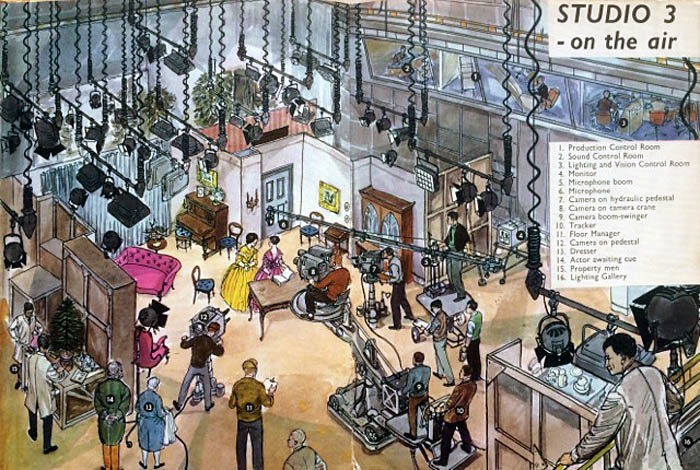

TC2 and TC5 were both 60 x 40 metric feet within firelanes and TC3 and TC4 about 90 x 70 metric feet within firelanes.

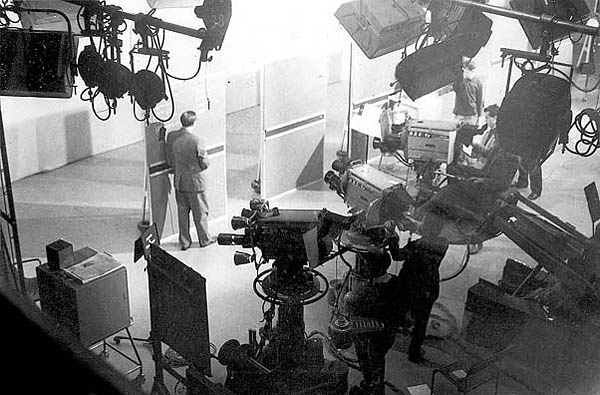

Incidentally, the large window slightly protruding into the studio on top left of the picture is the viewing gallery. Every studio had one of these (even control room suites did originally.) The idea was that visitors could be brought round to see ‘their’ BBC in action without disturbing what was going on.

This still went on right to the close, believe it or not. More than once I found myself standing in the middle of an empty studio set waiting for the sparks to return from lunch whilst picking my nose and scratching my behind – only to idly look up and focus on a window with 20 bemused members of the Women’s Institute gazing down at me.

image thanks to Richard Broadhurst and the Tech-Ops website

image thanks to Roger Bunce

photo thanks to Geoff Fletcher

image thanks to Ron Green and the Tech-Ops website

Of the larger two original studios, TC3 was earmarked as a drama studio and TC4 for light entertainment. The difference was in the acoustic treatment of the walls – TC3 had a shorter reverberation period so was more suited to speech. I have to say that I was never aware of this, having worked on many occasions in both studios, so possibly any acoustic difference was altered in later years. (Both studios in any case had new acoustic wall panels fitted following the removal of asbestos – TC4 in 1988 and TC3 in 2007.) Anyway, during the early years at least, TC3 was the preferred studio for drama.

TC4 also had a variable acoustic system involving microphones and speakers around the roof and walls. This was called ‘ambiophonics’. The system is said to have worked quite well, but according to a sound supervisor of the time it had the disadvantage that the delays to the different speakers would only be correct for one position within the orchestra. That (and probably the scarcity of such programmes) meant that it fell into disuse. It was soon overtaken by artificial electronic reverberation systems, although interestingly, a similar system was included in Limehouse studio 1 when that was built in 1982.

photo thanks to Bill Jenkin

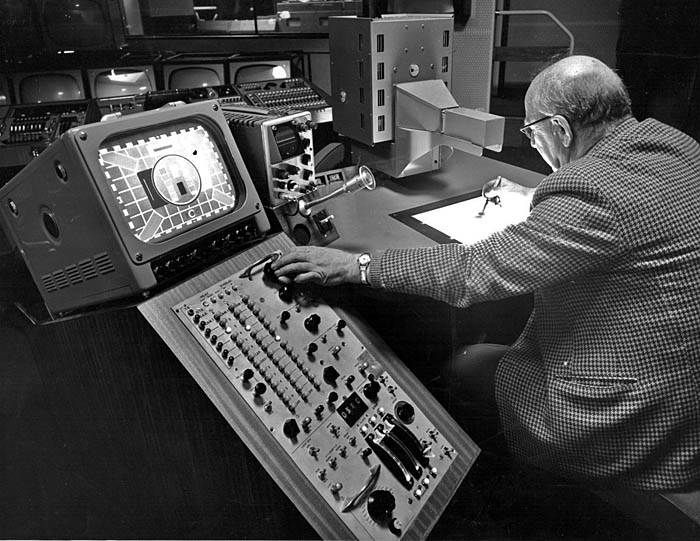

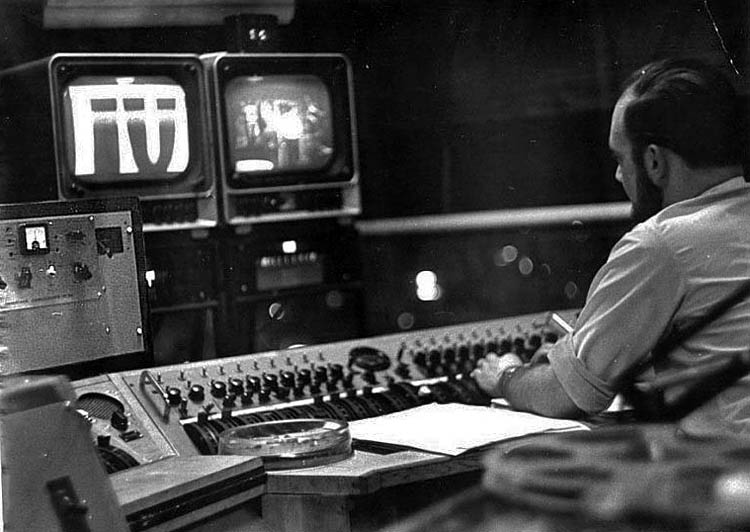

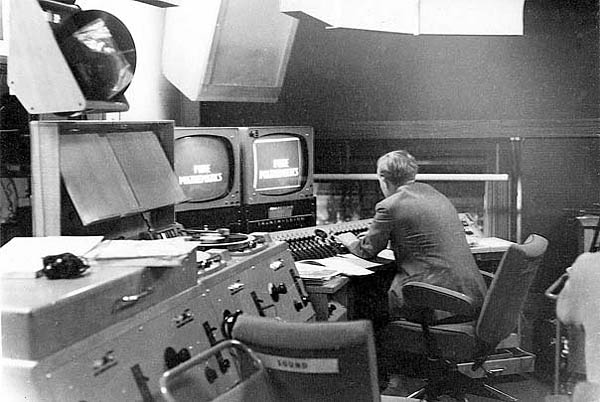

The desk was placed in the production gallery. All the BBC’s main studios had one of these. They enabled clever wipes to be used or an early form of overlay using a luminance key. The device seen to the right of the operator here is a camera looking down at an illuminated screen. You could place a piece of black card in the shape of, say, a flower and that could be used as a key for an effect in a dance routine. All kinds of wipes were tried out. A particularly messy one was to cover the screen with tealeaves and blow them off on cue. You couldn’t do that one again in a hurry.

Later, as the studios were colourised the inlay desks became more sophisticated to include up to three layers of CSO (colour separation overlay). DVEs (digital video effects) were added as soon as they became available in the 1980s. The BBC research department came up with an early version but this was soon superseded by boxes manufactured by companies like Quantel. Top of the Pops usually tried these devices out first but within a few months every show was plagued with zooming, flipping and tumbling pictures for no good reason.

Nowadays wipes and overlay tricks are done by the studio’s vision mixer (switcher). Most complex video trickery is now done in post production rather than in the studio at the time of recording. Sadly, there’s no place any more for the ‘blowing the tealeaves across the screen’ wipe.

All the studios were fitted with one of these mimics but only TC1 and TC3 kept theirs up to closure in 2013. In the other studios it was replaced with a monitor display fed from the console, not the dimmers, which was nothing like as clear to read. It must have cost a fortune to connect around 1000 tiny lightbulbs for the mimic in TC1 – one to each dimmer.

Judging by the shape of the mimic – this must be TC3.

image thanks to the Tech-Ops website

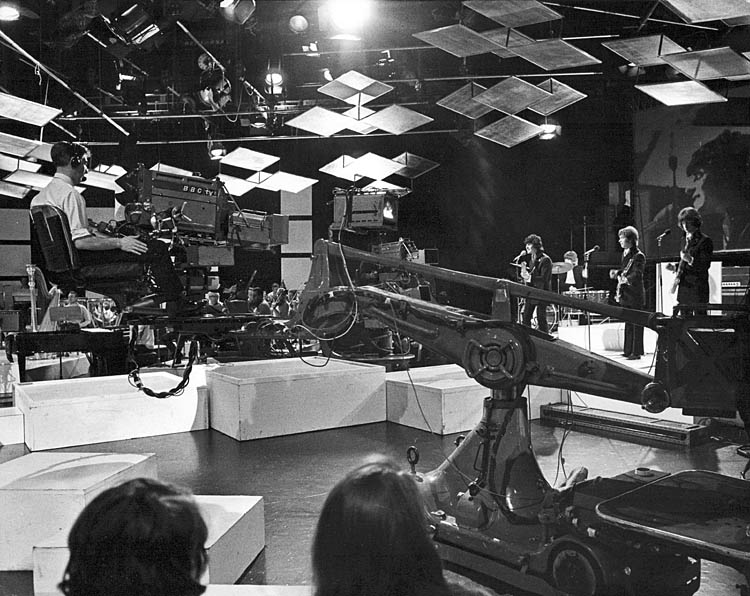

In 1960 the original camera choice was interesting. No doubt in a desire to support both major British camera manufacturers, half the studios – TC2, 3 and 7 – were equipped with Marconi Mk IV cameras and the other half – TC1, 4 and 5 with EMI 203 cameras.

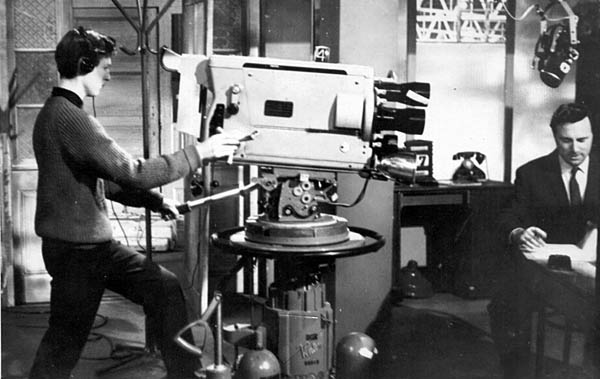

Thanks to Bernie Newnham for the image – for it is he – and a fine looking corduroy jacket it is too.

I have been given an interesting recollection by a cameraman of the period. He informs me that the EMI lens turret was designed for 5 lenses (although only four were fitted) and apparently was slower in changing lenses than the Marconi – particularly when going between the ones that involved crossing the blank plate. Apparently, for light entertainment this was seldom an issue but for drama it could be crucial. In a scene with two cameras taking over-shoulder 2-shots until the crucial dramatic moment when a close-up was called for, there might only be one second when the vision mixer cut to the other camera for the reaction shot before cutting back for the close-up. If the turret was still turning then the cut would be forced to be late. There was at least one drama director of the day who allegedly refused to work in the studio with the slower turret because it compromised his shooting style. His plays or episodes of drama series had upwards of 500 shots in half an hour.

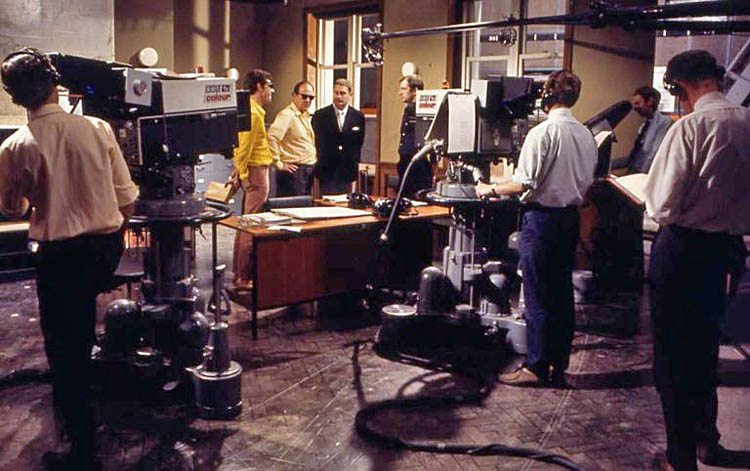

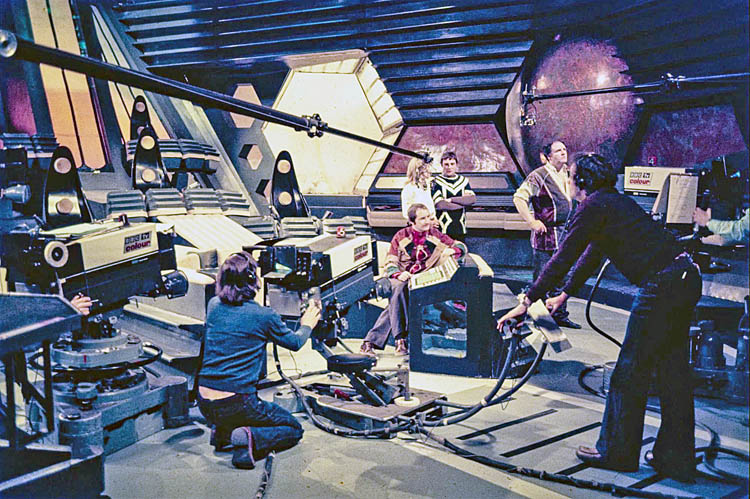

TC3 and 4 were both originally equipped with black and white cameras but the Centre had been planned with colour in mind. These two studios were re-equipped in 1969 and 1970 respectively with EMI 2001 colour cameras. Both studios in their last years had very swish gallery suites. TC4 was fully equipped for high definition in the summer of 2008 and TC3 in 2011.

photo thanks to Bob Glaister and the Tech-Ops website.

photo copyright Colin Davey, Evening Standard, Getty Images

photo thanks to Geoff Hawkes

photo thanks to Geoff Hawkes

photo thanks to Geoff Hawkes

Studios 3 and 4 were almost mirror images of each other although oddly, TC4 was actually 1 foot wider than TC3 at 71 metric feet within firelanes. This may be because the walls of TC3 were thicker in order to keep out the noise of the Hammersmith and City tube trains. By some quirk of fate there is a ‘whistle’ sign beside the track right by TV Centre so every train seemingly pointlessly gives that curious hoot that tube trains produce each time they pass the building. As testament to the designers of the building, this has never disturbed a recording.

The studios were equipped with the same design of long lighting bars as had been tried out in Riverside. Each was initially fitted with two 2kW fresnel lanterns and two multi-bulbed fill lights although this was adapted for each production. The lighting bars also at first had a parallel bar hanging a few feet beneath although quite how these were intended to be used remains a mystery. The bars were spaced the same as in Riverside – 2 feet from end to end and a whole six feet apart. This wide spacing has frequently caused many a headache to lighting directors, particularly when trying to position lights accurately over a drama or sitcom set. Although the bars were replaced with a new design in the 1980s the wide separation remained the same. In fact, when ITV took over TC3 in 2018 they installed extra trussing between the lighting bars to fill in the gaps.

These new studios adopted the dimming and lighting control systems that had been tried out at Riverside – Strand C-type consoles connected to variable resistor and auto-transformer dimmers, remotely controlled by an electro-magnetic clutch system. The heat generated by hundreds of these dimmers must have been phenomenal. Apparently, TV Centre was the first place to adopt normal mains voltage in the studios. Previously a voltage of 130 volts (I wonder why that particular voltage?) had been used. The BBC were also terribly proud of the fact that the lights in these new studios were ‘remote controlled.’

For someone who has become used to using automated lights like Vari-lites and Macs on various entertainment shows I found this claim somewhat surprising until I eventually found out what they meant. It seems that these were the first BBC studios equipped with luminaires that had attachments enabling an electrician to adjust pan, tilt, and spot and flood using a pole. Previously, every lamp had been adjusted by an electrician working off a set of ladders. I would hardly describe this as ‘remote control’ but seriously, this was a significant advance. I could work with an experienced pole operator to set 100 lamps and be finished in two or three hours. To do this using ladders would probably triple this time if not more.

The camera was balanced by pumping a handle and in theory the camera could be raised or lowered on shot but it was far from smooth. The tracker (in this instance, me) could simply push or pull and had to rely on a studio monitor somewhere in eye shot to frame a the picture. Usually the shot would be rehearsed so tape marks were stuck onto the floor. The front wheels could castor but if you had pushed in, you couldn’t then pull back as the dolly would wobble, ruining the shot – and the furious cameraman would get the blame and you would be given the cold shoulder for weeks afterwards. Not that that ever happened to me of course.

photo by Marty Johnston

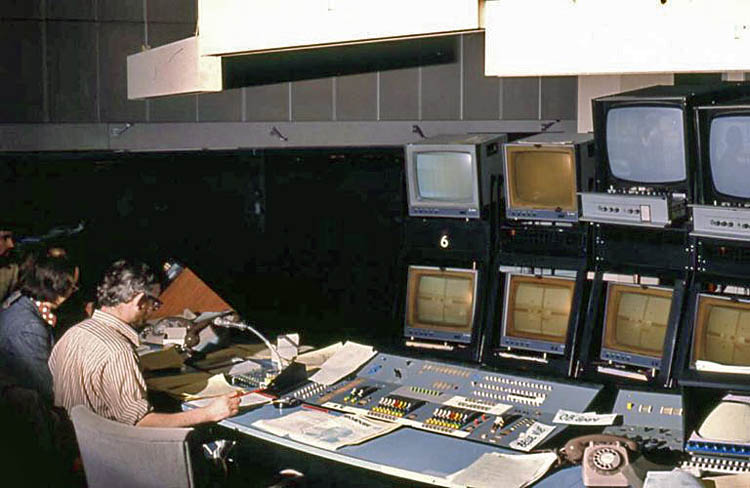

The three photos below were taken by Paul Holroyd in 2008, following a multi-million pound HD refit to TC4. It included a 5.1 surround sound mixer. The studio emerged as arguably the best equipped in the country. All the other main studios had similar refits – these were the ones you may remember were described by senior BBC managers as being ‘analogue dinosaurs in a digital age’ and by Michael Grade as needing 200 million pounds spent on them in order to bring them up to standard. Makes you weep, doesn’t it.

Of course, following the demolition of most of the building, only TC1, 2 and 3 remained. When these studios reopened ITV were quick to book TC2 and TC3. We will come to all this on a later page of this history but meanwhile, here are a couple of photos kindly sent to me of TC3 under the occupation of ITV Daytime.

photo thanks to Tom Smit

photo thanks to Tom Smit

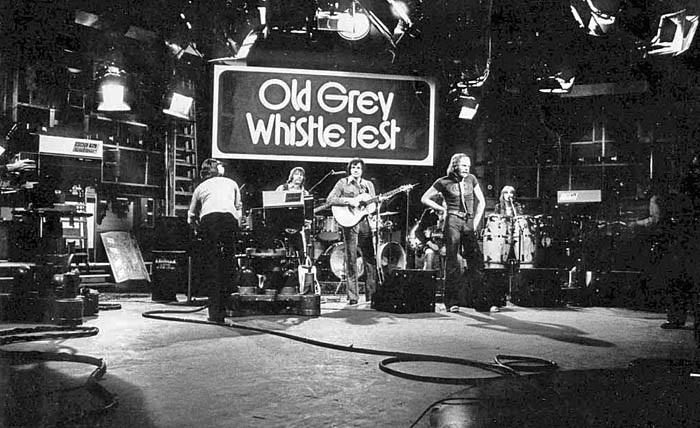

When it opened, TC2 soon became the home of the new wave of satirical comedy shows such as That Was The Week That Was (aka TW3) and The Frost Report.

image thanks to Keith Jacobsen and the Tech-Ops website

TC2 was also the home of a soap called Compact. It was transmitted on Tuesdays and Thursdays between January 1962 and July 1965. Set in the glamorous world of a fashion magazine, it was created by Hazel Adair and Peter Ling – who would later go on to make Crossroads for ATV. It was very popular but widely panned by critics. Some things don’t change.

image thanks to the Tech-Ops website

image thanks to the Tech-Ops website

photo thanks to Tony Grant

The rather sad photo below was taken by me in May 2015, two years after the Centre closed and two years before it was due to reopen. It is the production gallery of TC2. The window on the left looks through to the sound gallery, the one on the right is the viewing room. Astonishing as it seems now, every gallery at TVC (except TC8) originally had a window where members of the public could come and watch programmes being made (TC2’s was the only one to remain to the end). I think visitors would have found several programmes rather educational over the years, particularly the arresting language used by some directors under stress.

TC2 was the only studio not to have its galleries completely rebuilt at some point. It was of course re-equipped from time to time but these wall surfaces and windows are the original, dating back to 1960. Glory be – they survived the refurb and in 2017 they remained, albeit with a fresh coat of paint.

TC5 (60 x 40ft within firelanes) was the last of the original four studios to open – in August 1961. For the first decade or so it was the home of schools broadcasting and according to a 1970 BBC booklet ‘adjacent to studio 5 is an area specially designed and serviced for schools programmes.’ I assume this refers to the old puppet studio which must have become some sort of preparation/graphics area. Other programmes were also made here but for various reasons, most likely because no schools could afford colour televisions in the early 1970s, TC5 was converted to colour long after the other studios – probably in 1973. Its cameras were the last version of the EMI 2001 with upgraded electronics and arguably produced the cleanest pictures.

photo thanks to John Howell and the Tech-Ops website

photo thanks to John Howell and the Tech-Ops website

photo thanks to Les Thorn and the Tech-Ops website

With TC2 closed between 1969 and 1981 and TC7 occupied with Play School and Swap Shop/Saturday Superstore, TC5 became the studio used for cookery shows, discussion programmes, magazine shows like The Holiday Programme and panel shows like Call My Bluff and Ask The Family.

The studio was mothballed around 1985 – reopening in 1987 with Link 125 cameras. Link 130s were originally specified but they had major issues with them. Ian Dalton tells me he was an engineer in TC5 and has written to me about his experience with the proposed new cameras. (There is much more about the Link 130 saga on the ‘Potted History of Early Colour Cameras’ page.)

‘The refit of TC5 for the Sports Department was an extremely long and complex one. At the time, it was mooted to have become the most complex studio in Western Europe. Right from the start, we were supposed to have Link 130s, the first studio at TVC to have them. Some time before acceptance tests were started on the new installation, I was sent to Wood Norton for a week’s engineering course on the 130.Wood Norton had 3 of them, but we soon discovered that although they said ‘130’ on the outside, all three were different internally, with different version boards and different software. The MSP took particular exception to one of them and I remember it took a few days to get them all cooperating. That said, I remember they produced remarkably good pictures from the 2/3″ tubes and they seemed stable enough once set up correctly.TC5 started the acceptance stage without any cameras and it soon became clear that Link was no more. At the last minute, a set of Link 125s was cobbled together from various places. I remember one came from Ireland and another from Belgium. The 130 was potentially streets better than the 125, but unfortunately it died with Link.’

Thus in 1987 TC5 became the home of BBC Sport, which was its only use until 2011 when Sport moved to Salford and the studio closed for good. For many years the floor was divided in two with black drapes. The lighting gallery became a second production gallery, so that different sport programmes at each end of the studio could go out on BBC1 and BBC2 simultaneously. The lighting gallery was moved downstairs into the technical store and most of the cameras were remote controlled – the operator sitting alongside the LD and racks operator.

The photo above shows a number of scaffold bars being stored. Unfortunately, these were occasionally dropped with a resounding clang that could be heard in any nearby studio, despite the excellent soundproofing. Many a recording was ruined by this sound. The other regular disturbance was the noise of drilling. TV Centre was always in a state of rebuilding or improvement somewhere or other. Nobody knew where the work was being done but you could guarantee that at the worst possible time in a tense drama, the distant sound of a powerful drill would suddenly intrude. ‘No Knocking’ notices were issued by productions for certain times of the day but these seemed to have little effect.

One great advantage all the studios at TVC had over London’s other TV studios was in the provision of motorised scenery hoists. In monopole studios a few motorised hoists are sometimes available but these have to be carried into position and placed where needed in the grid. Most scenery is therefore supported using hemp ropes and hauled up by hand. At TV Centre this was hardly ever necessary. Every studio had dozens of scene hoists that could be tracked into position and raised or lowered at the push of a button. The hook was attached to a steel line that was fixed to the flattage or ceiling piece that needed to be supported. This made scene setting here much quicker, simpler and probably safer – and arguably gave designers more flexibility with their sets. In TC3 and 4 each hoist was initially only trackable within a span of about 10 feet but during the major refurbs of the 1980s more were installed and they could then track across the whole studio between the lighting bars. This improved system was originally installed in TC1, 6 and 8. TC1 has even more hoists, some capable of supporting immense loads.

During the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, the Centre contained some extraordinary facilities, many of which most people working there probably had no idea existed. For example – Tim Dorney, engineer in News dept, has written to inform me that during the 1970s he discovered that there was a room at the base of the South Hall where grand pianos were stored. The door was never locked and he tells me that he passed many a lunch hour practicing on one of several beautiful instruments, all of which were always in perfect tune.